FAI in Hockey Players: Causes, Symptoms, and Recovery | Ghost Rehab

What is FAI? (Brief Anatomy of the Hip & Impingement)

- Definition: Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a condition where the bones of the hip joint are abnormally shaped. Because of this bony abnormality, the ball (femoral head) and socket (acetabulum) rub against each other during movement, causing pinching and irritation in the joint .

- Cam vs. Pincer: In FAI, extra bone spurs can form on either the femoral head/neck or the acetabular rim (or both). A cam impingement means a bump on the femoral head that grinds the cartilage inside the socket, while a pincer impingement means an overgrown rim of the socket that pinches the labrum between the bones . (Many athletes actually have a combined type with both cam and pincer features.)

- Joint Damage: The abnormal contact from these bony bumps prevents the hip from moving smoothly. Over time, repeated impingement can tear the acetabular labrum (the cartilage ring sealing the socket) and wear down the hip cartilage, potentially leading to early osteoarthritis . In other words, FAI can cause cumulative damage in the hip joint if not addressed.

Why Hockey Players Are Susceptible

- Skating Mechanics: Hockey involves aggressive hip movements – players repeatedly drive the hip into deep flexion with internal rotation (think of a skating stride or a goaltender’s butterfly save). These motions push the femoral neck against the socket edge. Hockey players often operate near the extremes of hip range, so any bony bump can impinge sooner. In fact, impingement pain in hockey is closely linked to the combined flexion/internal rotation positions that occur in skating and goalie maneuvers .

- High Prevalence of Cam Deformity: Research shows that hockey players have a very high rate of FAI-related hip shape changes. For example, over 85% of hips in NHL players show evidence of a cam deformity . One study found hockey athletes were 10 times more likely to have an enlarged femoral head-neck angle (a sign of cam impingement) on X-ray compared to non-hockey peers . This means that many hockey players develop the bony features of FAI, likely due to their sport.

- Youth Training & Bone Development: The teenage years are when the hip bones are still developing. Intense, repetitive skating during youth hockey (especially playing year-round with little rest) may contribute to the formation of cam bumps on the femur . In other words, the stress of hockey on an immature skeleton can spur extra bone growth (Wolf’s law: bone adapts to loads) over time. Studies have noted that the cam deformity tends to progress with age in youth players, suggesting the longer and harder a young athlete plays hockey, the more the hip may adapt in a maladaptive way .

- Not Always Symptomatic: Importantly, many hockey players with FAI-related bony changes have no symptoms. Studies of elite players show that these bone shape changes (cam/pincer) can be common but often asymptomatic . FAI becomes a problem when it causes pain or injury – specifically when the impingement leads to labral tears or cartilage damage. Once those occur, players will start experiencing the classic symptoms and performance issues.

Common Symptoms and Warning Signs

- Groin and Front-of-Hip Pain: The hallmark symptom of FAI is pain in the hip groin area. Players often describe a deep ache or sharp pain in the front of the hip/pelvic region. Pain is typically brought on by activity – for example, a hockey player might feel a pinch when skating hard, doing deep cross-overs, or after a long time on the ice. Movements like turning, pivoting, or squatting can trigger a sharp, stabbing pain in the groin, or sometimes just a persistent dull ache . Pain from FAI is usually felt in the groin, but it can also radiate to the side of the hip, buttock, or even into the thigh. Some athletes describe it like a deep bruise or pressure in the hip joint that gets worse with intense activity or after sitting with hips bent for a long time .

- Hip Stiffness and Limited Motion: FAI often causes a noticeable loss of hip mobility. Players might feel their hip is “tight” or doesn’t move as freely, especially in certain directions. Commonly, internal rotation (turning the thigh inward) and flexion (lifting the knee toward the chest) are limited. A hockey player might struggle with low skating stances or certain stretches that were previously easy. This stiffness can lead to a sense of decreased flexibility in the hips . Coaches may notice the athlete can’t stride as widely or skates with a more upright posture due to the restricted motion.

- Clicking, Catching, or Locking Sensation: Many with FAI (especially if it has caused a labral tear) experience mechanical symptoms in the hip. They may feel or hear a “click” or pop in the hip with movement. Some describe a momentary catching or locking of the hip joint – as if it gets stuck briefly and then releases. These sensations often occur when moving from a flexed position (like getting up from a deep crouch) or changing direction quickly. A clicking hip accompanied by pain is a warning sign that a labrum tear could be present .

- Pain with Sitting or Prolonged Positions: Because hip impingement is worst when the hip is bent, sitting for long periods (especially in a deep seat or with poor posture) can aggravate the pain. A player sitting on a bus ride or in class may feel increasing hip ache or stiffness. They might instinctively shift position or straighten the leg to relieve the discomfort. Pain may also flare after games or workouts, during rest, as inflammation sets in.

- Limping or Movement Changes: In some cases, players with significant hip impingement will limp or alter their mechanics to avoid pain. You might notice a player coming off the ice with a slight limp or taking shorter strides on one side. They might rotate their foot outward (external rotation) when walking or skating to circumvent the painful range of motion. Any unexplained limp or change in skating stride, combined with groin pain, should raise a flag for possible FAI.

- Red Flag – “C-sign”: Athletes with deep hip joint pain often make a C-shape with their hand and grip the upper thigh/hip to describe where it hurts (covering the hip joint with their thumb and index finger). This “C-sign” complaint (pain deep in the hip joint) is commonly associated with FAI and labral tears . If a player localizes pain by cupping the hip like this, it suggests the pain is inside the joint.

Risks of Untreated FAI

- Hip Labral Tears: If impingement is allowed to continue unchecked, the repetitive pinching can fray or tear the acetabular labrum (the ring of cartilage around the socket). A torn labrum causes more pain and hip instability – the labrum helps seal and stabilize the joint, so a tear can lead to catching sensations and further joint stress. Untreated FAI is one of the leading causes of labral tears in young athletes . What starts as a bony impingement problem can evolve into a soft tissue injury, compounding the issue.

- Cartilage Damage and Early Arthritis: The constant abnormal contact in the joint can wear down the articular cartilage that lines the hip socket and femoral head. Over time, this cartilage erosion can lead to osteoarthritis at an earlier age than normal. In fact, FAI is a known precursor to hip arthritis – the bone spurs literally grind the cartilage away. If a player’s FAI progresses to bone-on-bone contact, they could be at risk for arthritis in middle age or even earlier . This means an untreated impingement today might cause chronic arthritic pain and stiffness years down the line.

- Chronic Pain and Loss of Function: What may begin as occasional soreness can become a constant pain if FAI isn’t managed. Players might go from only having pain after games, to having pain during games, and eventually pain even with daily activities (like climbing stairs or tying shoes). Untreated FAI can significantly reduce quality of life – simple tasks can hurt, and athletic performance certainly declines. The longer painful symptoms go on, the more damage can accumulate in the joint . In the worst case, a player might have to stop sports entirely because of disabling hip pain.

- Reduced Performance: From an athletic standpoint, ignoring FAI symptoms can lead to measurable performance drops. The hip is a central power generator for skating; if it’s not moving well, the player’s stride and agility will suffer. Research on hockey players suggests that those with symptomatic FAI often show reduced hip strength and range of motion, which in turn negatively impacts their on-ice performance (speed, quick turns, etc.) . Players might notice they can’t skate as fast or shoot with as much torque because their hip won’t allow it. In high-level hockey, even a slight loss of motion or power can be the difference in performance.

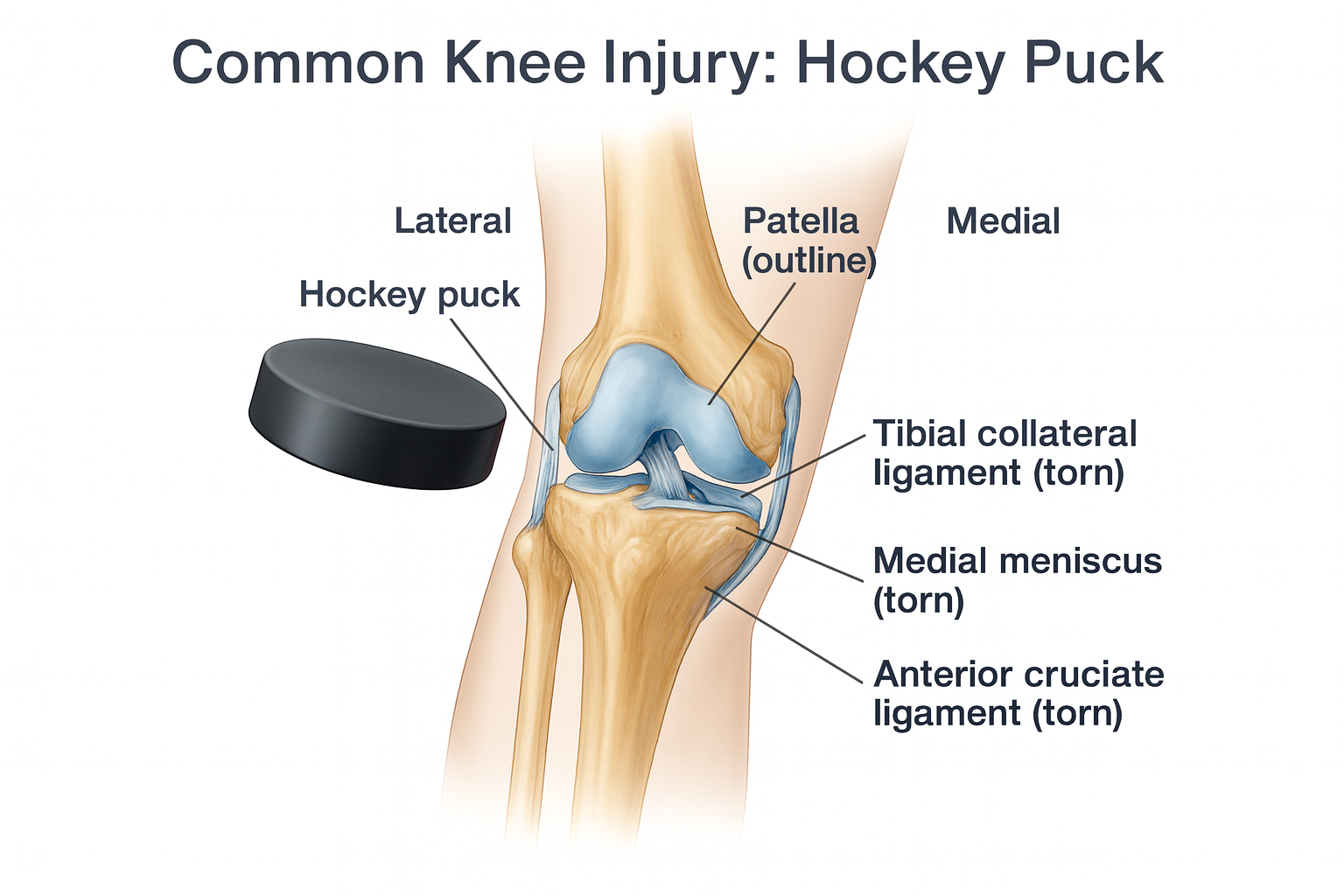

- Compensatory Injuries: When one part of the body isn’t functioning properly, other areas often compensate. Players with a chronically painful hip may overload their opposite hip, lower back, or knees to make up for it. This can lead to secondary issues like low back pain, muscle strains, or knee problems. For instance, a player might start using their back more to get low instead of their hips, risking back injury. Thus, untreated FAI can set off a chain reaction of injuries beyond the hip itself.

Prevention Strategies for FAI and Hip Injuries in Hockey

While you can’t change the shape of your bones without surgery, there are steps to minimize impingement risk and keep the hips healthy. Emphasizing preventative care is especially important for young players and those at high risk (e.g. history of groin/hip pain). Key strategies include:

- Thorough Warm-Up: Always begin practices and games with a proper dynamic warm-up that targets the hips. This should include light aerobic activity (jogging or easy skating), dynamic stretches (leg swings, lunges, hip circles), and sport-specific movements at low intensity. A warmed-up muscle and joint is more flexible and can move through a greater range. Warming up increases blood flow to the hip musculature and prepares the joint for the demands of skating, which may reduce the chance of pinching the joint early in a session. Cold, stiff hips are more likely to impinge, so never skip the warm-up.

- Hip Mobility Exercises: Incorporate regular mobility training for the hips into the fitness routine. This can include exercises to gently improve hip internal rotation and flexion range of motion. Examples: quadruped rock-backs (sitting back toward your heels to flex the hip, while keeping a neutral spine) – inability to do this can indicate a flexion blockage , deep lunge stretches, figure-4 stretch for piriformis, and adductor/groin stretches. Use controlled leg swings and hip rotations to maintain capsule flexibility. Mobility drills with resistance bands pulling on the hip (distraction) can also help ease impingement tension by creating space in the joint . By keeping the hip capsule and muscles flexible, you allow the joint to move without hitting an impingement end-range as quickly.

- Strengthen Supporting Muscles: Focus on strength training the muscles around the hip and core. Strong glutes, hamstrings, and core muscles help stabilize the pelvis and control the hip’s motion, potentially reducing the strain on the joint during extreme movements. In particular, strengthening the gluteal muscles (glute max and medius) can offload the front of the hip by ensuring you’re using your hips correctly (e.g., pushing through the heels and engaging glutes in skating strides). Core strength helps keep the pelvis in a good position (preventing excessive anterior pelvic tilt which can worsen impingement) . A well-designed conditioning program will include exercises like squats (avoiding going past painful range), lunges, hip bridges/thrusts, and planks – emphasizing form and pain-free execution. Balanced muscle strength can relieve stress on the hip joint by improving biomechanics .

- Avoid Overuse & Early Specialization: For youth hockey players, one of the best preventative strategies is to moderate their year-round load. Overuse is a big factor in developing FAI. Encourage young athletes to take an off-season or play multiple sports, rather than skating 12 months a year. Continuous hockey without rest can repeatedly stress the hip and encourage those bone changes. One study found an alarmingly high rate (over 75%) of hip changes in hockey players aged 16–18 who had been skating since they were toddlers . If it turns out that intense hockey during growth spurts is causing these bone adaptations, then limiting ice time and ensuring rest periods is crucial . Coaches and parents should be mindful of how many hours a week a young player is on the ice. Rest and cross-training can help the body recover and develop more uniformly, potentially reducing the risk of FAI development.

- Proper Technique and Coaching: Ensuring players use good skating and shooting technique can also help. For instance, a player who consistently uses a very wide stance or deep hip turnout might be putting extra impingement stress on the hips. Coaching adjustments to technique (within the bounds of effective play) might alleviate some unnecessary hip strain. Goalie coaches, in particular, should pay attention to how often and how early young goalies are dropping into full splits or extreme butterfly positions – scaling training appropriately to hip maturity.

- Listen to Early Warning Signs: Perhaps the most important “prevention” tip is to address symptoms early. If a player complains of chronic groin or hip pain, don’t push through it without evaluation. Pain is the body’s warning that something isn’t right. Ignoring mild impingement pain and continuing high-intensity play can turn a minor issue into a major injury. Encourage a culture where players report hip and groin soreness. Early rest or modification of training (for example, temporarily avoiding deep squats in the weight room if those provoke pain) can prevent a small labral fray from becoming a full tear . In short, never ignore hip or groin pain in a hockey player. It’s far better to lose a week of practice for rehab now than to lose an entire season (or career) later. As medical staff often note: the longer impingement symptoms go untreated, the more damage can occur in the joint . Prompt attention and rehab can keep a player on the ice long-term.

- Manage Posture Off the Ice: Hockey players often have tight hip flexors and an anterior pelvic tilt from the skating position. Off the ice, this posture can contribute to impingement. Teach players to avoid prolonged sitting in a hunched posture (which keeps hips flexed). Encourage them to stand up and stretch hip flexors if sitting for long periods (school, etc.). Simple habits like sitting with knees slightly lower than hips, or using a small cushion to support the low back, can reduce constant hip flexion angles off the ice. The idea is to give the hip a break from impingement positions during daily life as well . Similarly, working on posterior chain flexibility (hamstrings, glutes) and core strength will improve pelvic alignment. Good posture and ergonomics can complement other prevention efforts.

Diagnosis of FAI in Players

- Clinical Evaluation: When FAI is suspected, a healthcare provider (typically an orthopaedic surgeon or sports medicine physician) will take a history and perform a physical exam of the hip. A classic test is the “impingement test” (FADIR) – the examiner flexes the hip to 90° (bringing the knee toward the chest), then adducts and internally rotates the hip (turning the knee inward across the body). If this maneuver reproduces the sharp groin pain, the test is positive for impingement . Doctors will also check hip range of motion in all directions, compare one side to the other, and assess for pain with other movements (like FABER test – flexion/abduction/external rotation). They may observe the patient’s gait or skating motion (if possible) to see any limp or restriction.

- Imaging Tests: To confirm FAI and plan treatment, imaging is crucial. X-rays of the hip can reveal the telltale bony shapes – for example, an abnormally large femoral head-neck junction (cam bump) or an overextended acetabular rim (pincer spur). The presence of a cam lesion is often quantified by the alpha angle on X-ray; an alpha angle above ~55° is a common criterion indicating a cam-type impingement . X-rays also help evaluate if there are signs of arthritis (like joint space narrowing). Additionally, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be ordered, especially if a labral tear is suspected. MRI (often with an injected contrast, called MRA) can visualize the labrum and cartilage. A labral tear or cartilage damage caused by FAI will usually show up on MRI. In some cases, CT scans are used for detailed 3D bone anatomy if surgery is being planned, to map out the exact shape of deformities.

- Diagnostic Injection: Sometimes doctors use a local anesthetic injection into the hip joint to confirm the diagnosis. If numbing medicine is injected into the joint under imaging guidance and it temporarily relieves the pain, it suggests the pain is indeed coming from inside the hip (likely FAI/labrum) rather than from muscles or other sources. Often a corticosteroid is combined with the anesthetic to also reduce inflammation. An injection can thus be diagnostic and therapeutic – if a player gets significant relief for a time after the injection, it reinforces that FAI is the cause of pain . (Note: repeated steroid injections are generally avoided in young athletes, as they can weaken tissues; this is usually a one-time or occasional diagnostic tool.)

Treatment Options: Conservative and Surgical

Conservative (Non-Surgical) Management:

- Rest and Activity Modification: The first line of treatment for FAI is often simply changing activities to avoid painful movements. The athlete may need to take a break from hockey or cut down training volume in the short term to let the hip calm down. Coaches can modify drills so the player isn’t forced into extreme ranges (for example, limiting deep skating drills or avoiding certain stretches that hurt). Often, avoiding sitting in deep flexion (like deep crouches) and steering clear of exercises that provoke pain (full squats, heavy deadlifts from the floor) is advised . This doesn’t mean the player can’t do anything – it means training smarter, not harder, while symptoms persist.

- Physical Therapy (PT): A targeted physical therapy program is crucial for most athletes with FAI. The goals of PT are to improve hip range of motion, strengthen the surrounding muscles, and correct movement patterns that might be exacerbating the impingement. A therapist will typically work on stretching tight structures (like hip flexors, IT band, glutes) and guiding the athlete through exercises to strengthen the glutes, core, and hip rotators. By increasing flexibility and strength in the right areas, PT can reduce stress on the injured labrum or cartilage, often alleviating pain . Therapists also train athletes to avoid compensatory movements – teaching proper hip hinge, proper skating form, etc. Over time, many players can return to play after a course of PT, with improved mechanics and reduced pain.

- Medications: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), like ibuprofen or naproxen, are often recommended to help with pain and reduce inflammation in the joint. These can be particularly useful in the acute phase or after intense activity. They are not a long-term solution, but can make an irritated hip more comfortable as other treatments take effect . Always use under guidance of a doctor, especially for younger athletes, and watch for side effects (stomach upset, etc.).

- Injections: If rest, therapy, and NSAIDs aren’t sufficiently relieving the pain, a doctor might recommend a corticosteroid injection into the hip joint (often done with imaging guidance to ensure proper placement). The steroid is a strong anti-inflammatory; an injection can provide significant relief of pain and reduce inflammation in the joint. It may also help a player participate in rehab more comfortably. However, this is usually a temporary fix – the effects can last for weeks to a couple of months. It’s also worth noting that while injections can ease symptoms, they do not fix the underlying bone impingement; they are a way to manage symptoms or buy time in season. (As mentioned earlier, an anesthetic is usually given with the steroid, which can double as a diagnostic test for FAI .) Team physicians will usually limit how often cortisone injections are given in a hip due to potential side effects on tendons and cartilage with repeat doses.

- Ongoing Management: Some athletes with FAI can manage their condition long-term without surgery. This might involve continuing a dedicated routine of stretching and strengthening, modifying their training schedule to allow more recovery days for the hip, and being vigilant about any uptick in symptoms. They might also use modalities like ice, heat, or anti-inflammatory creams post-activity for relief. The key is that conservative management should keep the player’s pain at a minimal and manageable level while preserving or improving function. If despite these measures the pain is interfering with play or daily life, then more invasive options are considered.

Surgical Management:

- When Surgery is Considered: If an athlete has persistent hip pain from FAI that does not respond to conservative treatments, or if imaging shows significant damage (like a big labral tear or cartilage injury), surgery may be recommended . In high-level athletes or those with clear bony deformities, early surgery might be advised to prevent further damage. The decision comes down to quality of life and goals – for a competitive hockey player aiming to continue playing at a high level, surgery is often the definitive fix for symptomatic FAI.

- Hip Arthroscopy (FAI Surgery): The most common surgical approach for FAI today is arthroscopic hip surgery. This is a minimally invasive procedure where the surgeon makes 2-3 small incisions (portals) and inserts a camera and instruments into the hip joint. Through these tiny incisions, the surgeon can reshape the bones and repair soft tissues. Specifically, the surgeon will trim the bony prominences causing impingement – shaving down the cam bump on the femoral head and/or trimming the acetabular rim in a pincer lesion . They will also address any labrum or cartilage injury: the torn labrum can be repaired (stitched back to the acetabulum) or debrided (smoothed), and any frayed cartilage can be cleaned up. The goal is to restore a more normal hip shape so the femur can rotate freely without catching. Arthroscopic FAI surgery is typically done outpatient (no overnight hospital stay).

- Open Hip Surgery: In rare cases with very severe deformities, an open surgery (with a larger incision) might be needed, but this is uncommon now given advances in arthroscopy. Open surgery may also be needed if there is extensive arthritis (sometimes a different procedure or even hip replacement in older individuals, though that’s beyond athletic scenarios). For most hockey players, arthroscopy is the gold standard approach.

- Surgical Outcomes: The success rate for hip impingement surgery in athletes is quite high. Arthroscopic FAI correction can significantly reduce pain and improve function for the majority of patients. By fixing the impingement, it also helps prevent future damage to the joint that would have occurred with continued impingement . In the elite hockey world, studies have shown that over 90% of NHL players are able to return to play after hip arthroscopy for FAI, often within 6–8 months post-op . Many players not only come back, but do so at a performance level similar to before injury. The procedure is minimally invasive and, when done by experienced surgeons, has a low complication rate. Many athletes have no long-term limitations after recovery – aside from maybe avoiding the absolute extreme motions, they can skate, shoot, and train normally . However, it’s worth noting that if there was extensive cartilage damage before surgery, some symptoms (or risk of arthritis) might still persist. Surgery can correct the impingement, but it cannot fully “undo” any arthritis that has already started. Therefore, earlier intervention (before severe cartilage loss) tends to have the best outcomes. Overall, for a symptomatic player, hip arthroscopy is currently the most effective way to resolve FAI pain and allow a return to high-level hockey .

Returning to Play After FAI Treatment

Recovering from FAI and getting back on the ice is absolutely possible – most players do return to their sport – but it must be done carefully. Here are some tips and guidelines for return-to-play:

- Commit to Rehabilitation: The rehab process is the bridge between treatment (whether surgery or conservative) and playing again. Adhering to your physical therapy and rehab program is crucial. This will involve exercises to restore your hip’s range of motion, increase strength, and retrain balance and coordination. Early on, focus is on gentle range-of-motion exercises and reducing inflammation. Then it progresses to strength training (core, glutes, hip muscles) and eventually skating-specific drills. It’s important for the athlete to not skip steps – even if you feel okay, continue to follow the physio’s plan to ensure all aspects of hip function are fully restored. Remember that after surgery, there’s healing that must occur (bone and tissue need to heal), so there are phases where certain movements are restricted for a while. Rushing back too soon can jeopardize the repair. Think of rehab as part of your training; attack it with the same intensity and focus as you would a workout or practice.

- Gradual On-Ice Progression: Returning to hockey should be done in phases. Even after you’re cleared to start skating, it should be a stepwise increase in intensity and complexity. For example, you might start with light skating or stickhandling drills with no contact. If that goes well (no pain or swelling later), you progress to more intense skating, like sprint drills or direction changes. Next might be practice in full gear but without full contact scrimmage. Then controlled contact drills, and finally full scrimmage and game situations. This progression could span several weeks. A guideline often used is: you must be able to complete each step pain-free (or with only mild soreness) before advancing to the next. If a certain level causes pain, you scale back and stay at that level a bit longer. This graduated approach ensures you’re not overloading the healing hip.

- Criteria for Full Return: Sports medicine professionals now often use criteria-based benchmarks to decide if an athlete is ready for full return to play, rather than just an arbitrary timeline. Some criteria include: achieving near-normal hip range of motion compared to the uninjured side, at least 90% strength of the hip musculature (often measured in the clinic with specific tests), and the ability to perform sport-specific movements at full speed without pain. There are also functional tests – for instance, one group developed a “Vail Hip Sports Test” which includes single-leg squats, lateral movements, and other dynamic tasks to gauge the hip’s readiness . Athletes may also fill out questionnaires about confidence in the hip. All of these help ensure that when you go back to competition, you’re truly ready and at low risk of re-injury. Practically speaking, clearance will be a team decision: the surgeon/doctor examines the hip, the physical therapist/athletic trainer tests your function, and you, as the athlete, report how you feel. Only when everyone is confident should you return to full play.

- Typical Timeline: Recovery time varies per individual. For conservative treatment (no surgery), a player might rehab for several weeks to a couple of months until symptoms are controlled and then return if pain allows. After hip arthroscopy, timelines are often on the order of a few months: many athletes are jogging or doing light skating by 3–4 months post-op, and return to competitive play usually between 4 to 8 months after surgery, depending on the extent of repairs and the demands of their position. High-level hockey players tend to push toward the earlier side (5–6 months), but it really must be individualized. Studies of professionals report that over 90% of players return to sport within one year of surgery, with the average around 6–7 months . Patience is key: coming back too early can lead to setbacks, whereas taking the time to properly heal and train means you’ll come back stronger and more durable.

- Psychological Readiness: Don’t overlook the mental aspect of returning from a hip injury. It’s common to have some anxiety about whether the hip will hold up, or to subconsciously guard your movements. Part of rehab in later stages is doing sport-simulation drills to rebuild confidence. Working with trainers and possibly sports psychologists on mental strategies can help. You want to return to play mentally prepared and confident in your body, not second-guessing every move.

- Post-Return Maintenance: Once back in action, the work isn’t completely over. It’s wise to maintain the hip exercises that got you there – keep doing your stretching routine, your glute/core strengthening, etc., as part of your normal fitness program. This will help keep the impingement from flaring up again. Also, continue to communicate with coaching and medical staff about how the hip feels. Often, players will have periodic check-ins or maintenance physio sessions. Some might benefit from occasional manual therapy or massage to keep hip muscles limber. Essentially, you should treat your hip health as an ongoing priority. Many athletes incorporate dynamic warm-ups and cooldown stretching permanently after an injury, which in fact can enhance overall performance and injury prevention.

- Adjustments as Needed: In some cases, players may need to adapt certain things even after full return. For example, a goalie might alter their butterfly technique slightly to reduce extreme hip rotation, or a skater might adjust their training regimen to include more off-ice recovery. These adjustments are not a sign of weakness but of smart management – playing to your strengths while protecting a vulnerable area. Fortunately, after successful treatment, most players can perform at essentially the same level as before. Career longevity after FAI surgery is generally good; studies show players continue playing without a significantly shortened career on average . The bottom line is, returning to hockey after FAI is highly achievable. By following medical guidance, doing the rehab, and not rushing the process, players often come back feeling relief from pain and even improved hip mobility, which can enhance their game.

Key Takeaway

FAI is a common hip issue in hockey players due to the demands of the sport, but with awareness and proper management, its impact can be minimized. Educating players, coaches, and parents about the symptoms (like persistent groin pain and stiffness) and the importance of early intervention is crucial. Through prevention strategies (proper warm-ups, training balance, and not overloading young hips) we can reduce the occurrence of debilitating hip problems. And for those who do develop symptomatic FAI, modern diagnosis and treatment options – from targeted physio programs to advanced arthroscopic surgeries – offer excellent outcomes. With a structured rehab and return-to-play plan, hockey players with FAI can successfully get back to the sport they love, stronger and smarter about their hip health. Playing through pain is not a badge of honor when it comes to FAI; addressing it early prolongs careers and preserves quality of life . By having these talking points accessible, we empower the hockey community to recognize and react to FAI in a way that keeps athletes healthy and on the ice for the long term.

References

Powers CM, et al. (2020). Rehabilitation strategies for FAI and post-arthroscopy patients. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 50(3), 123–135.

Ayeni OR, et al. (2012). Femoroacetabular impingement in elite ice hockey players. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 94(10), e58.

Agricola R, et al. (2013). Development of Cam-type deformity in adolescent and young male soccer players: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med, 42(4), 798–806.

Philippon MJ, et al. (2014). The prevalence of cam-type deformity in high-level youth hockey players. Am J Sports Med, 41(6), 1357–1361.

Siebenrock KA, et al. (2011). The cam-type deformity of the proximal femur arises in childhood in response to vigorous sporting activity. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 469(11), 3229–3240.

Larson CM, et al. (2013). Radiographic prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement in collegiate and professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med, 41(1), 134–138.

Economopoulos KJ, et al. (2015). The effect of skating posture on hip joint loading during on-ice skating in hockey players. Clin Biomech, 30(6), 589–594.

Clohisy JC, et al. (2008). A systematic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of FAI. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 16(9), 561–570.

Ganz R, et al. (2003). Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 417, 112–120.

Beck M, et al. (2005). The anatomy and function of the labrum in the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 429, 16–23.

Byrd JWT. (2005). Hip arthroscopy in athletes. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, 13(2), 78–88.

Kuhns BD, et al. (2015). Outcomes after hip arthroscopy in elite athletes: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med, 43(1), 1–8.

Domb BG, et al. (2014). Return to sport after hip arthroscopy in elite athletes. Am J Sports Med, 42(1), 180–185.

Kivlan BR, et al. (2011). Relationship between lower extremity mechanics and patient-reported outcomes in athletes with FAI. J Sport Rehabil, 20(4), 457–471.

Menge TJ, et al. (2017). Outcomes of hip arthroscopy in competitive hockey players: return to sport and performance metrics. Orthop J Sports Med, 5(2), 2325967116689490.

Agricola R, et al. (2014). Cam impingement and the development of osteoarthritis of the hip. Orthop Clin North Am, 44(4), 449–461.

Kelly BT, et al. (2005). Arthroscopic labral repair in the hip: surgical technique and review of literature. Arthroscopy, 21(12), 1496–1504.

Takla A, et al. (2020). Physical examination and imaging of the hip in athletes. Clin Sports Med, 39(2), 163–179.

Khan M, et al. (2016). Predictors of outcomes after hip arthroscopy for FAI. Sports Health, 8(2), 141–148.

Nepple JJ, et al. (2013). The hip fluid seal—Part I: the role of labral and cartilaginous structures in hip stability. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 471(4), 1138–1143.

Reiman MP, et al. (2015). Femoroacetabular impingement surgery, rehabilitation, and return to sport: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 10(4), 547–565.

Scott EJ, et al. (2021). Return to sport after femoroacetabular impingement surgery in high-level athletes: a comprehensive review. Arthroscopy Sports Med Rehabil, 3(2), e423–e430.

Casartelli NC, et al. (2015). The hip sports activity scale: development and validation. Am J Sports Med, 43(4), 826–832.

LaPrade RF, et al. (2020). A sports physical therapy approach to FAI and hip arthroscopy. Sports Health, 12(2), 122–130.

Menge TJ, Briggs KK, Philippon MJ. (2017). Survival and performance of professional athletes after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med, 45(6), 1442–1448.

Larson CM, et al. (2010). Functional testing in FAI: the Vail Hip Sports Test. Orthop J Sports Med, 2(1), 11–17.

Fabricant PD, et al. (2015). Early outcomes after hip arthroscopy for FAI in athletes under 18 years of age. J Pediatr Orthop, 35(2), 123–129.

Feeley BT, et al. (2016). Return to elite-level play after hip arthroscopy among NHL players. Orthop J Sports Med, 4(3), 2325967116632752.

Sampson TG. (2005). Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 441, 222–229.

Philippon MJ, et al. (2007). Arthroscopic labral repair and treatment of FAI: minimum 2-year follow-up. Orthopedics, 30(8), 647–652.

Krych AJ, et al. (2013). Diagnostic hip injections: efficacy, accuracy, and indications. Clin Sports Med, 32(3), 411–419.

Tijssen M, et al. (2016). Conservative treatment of FAI: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med, 50(19), 1219–1226.

de Sa D, et al. (2015). Hip arthroscopy for FAI: a review of clinical outcomes and return to sport. Sports Health, 7(3), 268–272.

Notzli HP, et al. (2002). MRI of the femoral head-neck junction in FAI. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 418, 67–73.

Byrd JWT, Jones KS. (2011). Hip arthroscopy in athletes: 10-year outcomes. Am J Sports Med, 39(1), 117–123.

O’Donnell J, et al. (2021). Femoroacetabular impingement: current concepts and controversies. J ISAKOS, 6(4), 172–180.

Sansone M, et al. (2016). Predictors of outcome after hip arthroscopy in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 24(10), 3356–3362.

Ayeni OR, et al. (2014). Femoroacetabular impingement in young athletes: a review. Clin J Sport Med, 24(6), 464–470.

.png)